Fear of economic ‘lost decade’ hangs over world leaders in Washington

Tensions are rising, with rich nations furiously hiking interest rates to kill inflation but creating crushing debt burdens in the developing world.

Global finance ministers and central bankers will descend on Washington in the coming days amid economic turmoil that could tip the world into recession. And they will struggle to mount a coordinated response.

The war in Ukraine, stubbornly high inflation, rising interest rates, a fragile banking system and slower growth in China are all looming threats.

There are also growing tensions among nations, with wealthy countries furiously hiking interest rates to kill soaring prices but creating crushing debt burdens in the developing world. China is competing for influence with the U.S. and the EU, which are facing their own conflicts over trade. And Russia's geopolitical role continues to sharply divide governments.

"It's going to be chaotic," said Douglas Rediker, who represented the U.S. on the board of the International Monetary Fund from 2010 to 2012.

Underscoring the budding fears, the World Bank last month warned of a looming “lost decade” for the economy that could sap momentum for fighting poverty and addressing climate change.

The expanding list of economic uncertainties will pervade next week’s spring meetings of the IMF and the World Bank just a few blocks from the White House, setting up major challenges for leaders as they grapple with food and energy constraints, severe debt loads on developing countries and global warming.

“There’s going to be a great deal of hand-wringing with the state of the global economy,” said Mark Sobel, U.S. chair at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum and a former Treasury Department official who served as U.S. representative to the IMF. “A lot of perplexing questions. A lot of fog.”

Rediker described the mood as "disjointed."

"There are a lot of different threads going into these meetings and they're not necessarily harmonized in one narrative," said Rediker, managing partner at International Capital Strategies. "You've got them all happening at once at a time when there's no particular leadership that is driving the agenda or the narrative in one direction or another."

U.S. officials, led by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, will try to project cautious optimism but will also face questions about the government’s response to last month’s regional bank failures and to what extent there is potential spillover in the global economy, especially as lenders tighten credit for businesses.

“You don’t have any real motor of growth,” said Liliana Rojas-Suarez, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development. “It’s not that it’s one region that is weaker than the other. Wherever you look, growth is really low, and so of course that affects everything else.”

The U.S. economy is expected to grow by a tepid 0.4 percent this year, according to the Federal Reserve, before modestly accelerating to 1.2 percent in 2024. The Fed has driven the slowdown with the steepest interest rate hikes in four decades designed to tame inflation.

“There’s a fundamental challenge for the U.S., which is first and foremost it’s coming there speaking about growth in its economy, how it’s doing relatively well compared to the other advanced economies,” said Josh Lipsky, senior director at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a former adviser to the IMF.

Growth prospects in Europe are uncertain as it also deals with a roiled banking industry. The European Union managed to weather the winter better than expected and skirt a recession thanks to a drop in energy prices that had reached eye-popping highs last summer.

But core measures of inflation keep rising, and the ensuing fast-and-furious tightening of the money supply by the European Central Bank spells worries for the bloc’s outlook.

The EU economy is expected to stagnate this year below 1 percentage point of growth, hitting the brakes after posting 3.5 percent last year — higher than both the U.S. and China.

“I don’t think the IMF meetings are going to be in a hopeful mood — it’s going to be kind of depressing,” Rojas-Suarez said. “People are going to pull up good potential outcomes — like, the stock market is recovering, financial contagion seems to have moderated, the markets are relatively calm now. But at the same time, the sense of fragility in every corner that you turn is I think the mood that is going to be prevalent.”

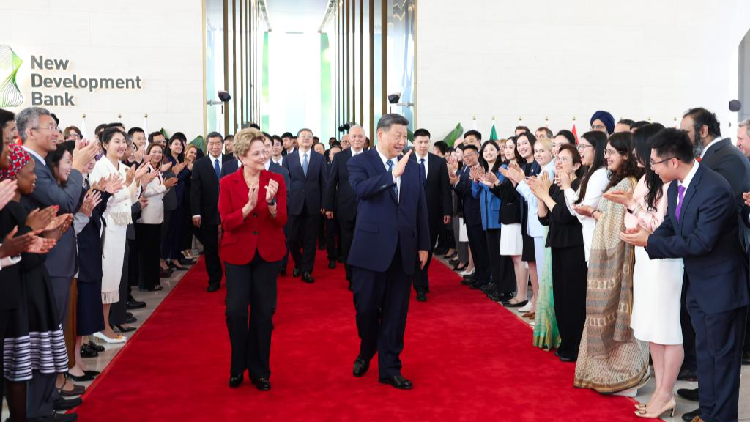

A major issue hovering over the meetings is the role of China, which just underwent a big government shakeup and is increasingly at odds with the U.S. over trade and technology. Questions include whether China should have a bigger say in the governance of international institutions commensurate with its economic power and whether it will help with efforts to ease the debt strain on developing countries, given that it's such a big lender.

"You get to a point where the very legitimacy of the institutions themselves gets challenged," Rediker said.

The World Trade Organization said Wednesday that global trade is expected to grow by 1.7 percent this year — a stronger outlook than it had in October. Still, it warned that the international economy is fragile, with commerce still recovering from Covid-19, continuing shockwaves from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and high inflation.

The World Bank — the international lender to developing countries — said last week that new policies are needed to boost productivity and accelerate investment to head off what could be a trying decade for the global economy.

The IMF on Wednesday separately warned that the world could lose trillions of dollars of future economic output if it splits into competing geopolitical factions.

The World Bank's outgoing president, David Malpass, says the global economy is suffering from stagflation – meaning low growth with stubborn price inflation. He said at an Atlantic Council event Tuesday that the U.S. and China have rebounded but that there needs to be much more production and productivity to break out of stagflation.

That comes as the world experiences what he describes as a “reversal in development," with rising poverty and worsening literacy problems.

“If you look at things today, the challenge is that there may not be progress,” Malpass said. “We need to avoid that lost decade.”

Paola Tamma contributed to this report.

Find more stories on the environment and climate change on TROIB/Planet Health