Want to know if a red wave is happening? Watch this special election.

The ultimate bellwether race — testing the potency of inflation vs. abortion as campaign focal points — is about to be decided in upstate New York.

WOODSTOCK, N.Y. — A special election here next week could offer Democrats a preview of the pain coming their way in November. Or it could provide powerful evidence that a Republican wave election is not in the offing.

Both parties are dumping money into this Hudson Valley district to notch a short-lived but symbolic victory in the last competitive race before the midterms. The winner will succeed Democrat Antonio Delgado for just a few months. But the messaging, turnout and margin of the contest will offer tea leaves into what lies ahead this fall in the battle for control of the House.

For Democrats, a win would offer proof that the party can translate their recent legislative victories and voter anger over the Supreme Court’s abortion ruling into tangible gains. After non-stop attention on their stalled policy agenda, internecine bickering and dire polling, Democrats are desperate to tell a different story.

“A win here would validate that the ground is shifting,” Pat Ryan, the Democratic nominee, said in an interview after a campaign event here with some three dozen supporters. “Democrats are really good at being hard on ourselves and we've been doing an awful lot of that. And sometimes you need to zoom out.”

“It will, maybe not reset, but I think certainly fundamentally reshape the trajectory,” he said.

Republicans have just as much riding on the outcome. Flipping the district would calm fears that the party peaked three months too early. Despite some evidence of an awakened Democratic base, operatives remain convinced that few down-ballot candidates can outrun President Joe Biden’s unpopularity, especially in this sprawling district, which unites the liberal towns north of New York City with struggling farm communities a hundred miles away.

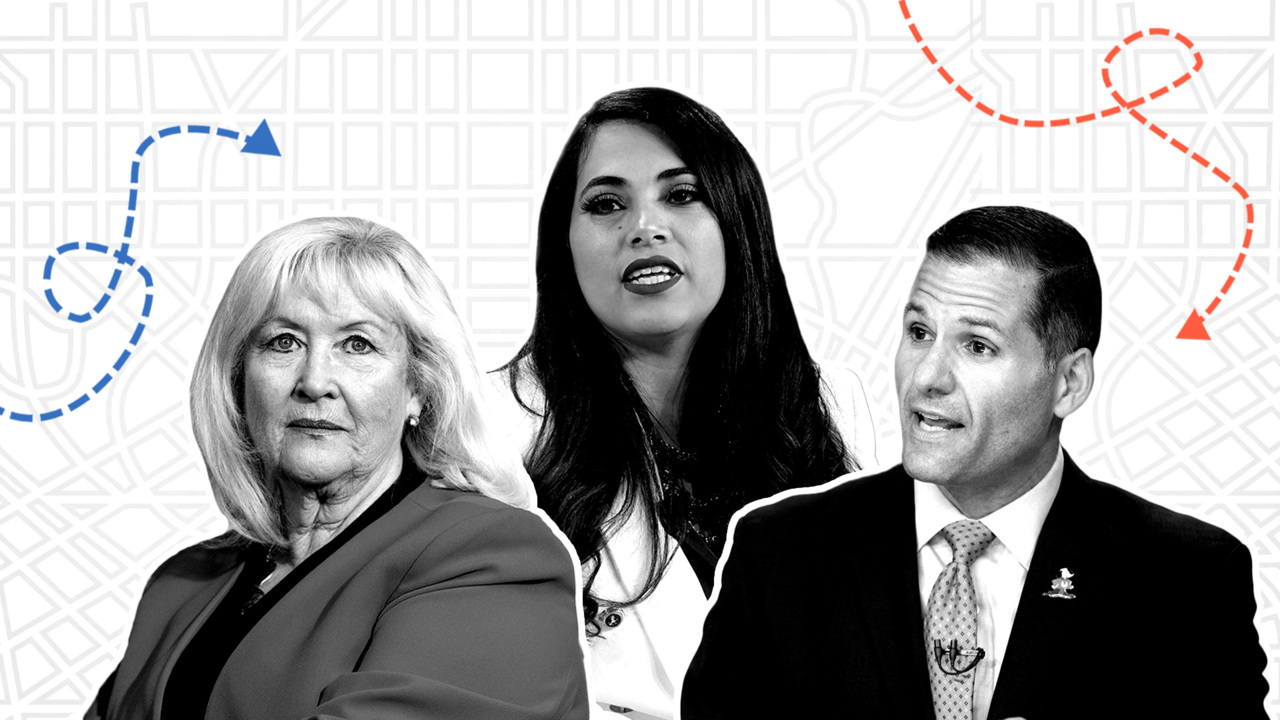

The matchup in the 19th district, which Biden carried by less than 2 points in 2020, is between Ryan, an Army veteran and Ulster County executive who has campaigned aggressively on abortion rights, and Marc Molinaro, the Dutchess County executive who has framed his bid as a referendum on the Biden administration’s economic failures. He has rejected any attempt by Democrats to redirect the conversation.

“What should be learned is this: When politicians and candidates try to dictate to voters what they believe their issues should be, those candidates should lose,” Molinaro said.

The candidates’ diverging focuses were on stark display in the final week of the race.

Campaigning in the storied liberal enclave of Woodstock, Ryan described recent events that he felt had helped build momentum for his party and campaign. Among them: “seismic Supreme Court decisions” that sided with conservatives on abortion, gun rights and environmental protections; and the rejection of a voter referendum to do away with abortion rights in red-leaning Kansas.

“We will send another message as the national spotlight starts to shift to us,” Ryan said. “Think about the message sent in Kansas, think about the message we can send right here.”

A day earlier and roughly 100 miles north, Molinaro heard from a vastly different swath of the electorate. The former GOP governor nominee joined Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.) and other local Republican officials at a tour of the Shults Family Farm in the small town of Canajoharie to discuss the economic turmoil choking their business. Among the concerning topics: Rising rent at the farmers’ market, the pain of inflation, volatile wholesale milk prices and government red tape hampering their sales.

Later, after a rally in a neighboring town, Molinaro took thinly veiled shots at Ryan and his allies for emphasizing abortion rights in their messaging.

“This is a special election. It is about the voters of the 19th Congressional District. And it is both disingenuous and a bit insulting to tell them what their issues are,” he said, pointing to other topics, like the economy and crime. “They are fearful for the future and they are concerned about their safety. I hear it everywhere.”

The election Tuesday is a true toss up, according to operatives in both parties. Public polling has been scarce and private party surveys have varied widely because special-election turnout is so difficult to predict. The race will coincide with some of the state’s primaries but independents — who will determine many close races this fall — cannot vote in nominating contests.

Republicans have outspent Ryan and his allies by nearly $1 million on TV, according to the media tracking firm AdImpact. But Ryan has received a late boost from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and VoteVets, both of which are running ads focused on abortion rights.

In many ways, Ryan is piloting an early test whether or not access to abortion can sway competitive congressional races. When the Dobbs ruling was issued, he quickly used his paid advertising on TV and in the mail to stress his commitment to abortion access. It wasn’t even a discussion whether to do so, Ryan said in an interview.

He said Democratic base and independent voters he encounters on the campaign trail are responding to the issue.

But Molinaro, who was once the youngest mayor in America, has pointedly tried to keep the conversation away from abortion, running a playbook used by several other GOP candidates running in purple districts.

Citing his personal experience growing up on food stamps, Molinaro said an abortion-focused campaign does “a disservice” to the thousands of families “talking desperately about how are they going to survive tomorrow.”

Democrats have accused Molinaro of shifting his position on abortion rights based on the political winds. During his 2018 statewide run, he said he would support a move to strengthen the state’s protections for the right to an abortion, which he considered to be settled law. Now he frames it as an issue that should be decided on a state-by-state basis with little role for Congress.

“They have a problem with acknowledging the obvious,” Molinaro said of Democrats, noting his stance changed with the Supreme Court’s ruling. “My view is the federal government's role is exceptionally limited.”

Democrats can and should discuss both economic issues and abortion access, Ryan said, but the latter has been more salient: “We are talking about both, but what is more resonant in my discussions, actually, is reproductive freedom.”

It’s possible both Ryan and Molinaro end up in Congress by 2023 because of a quirk in redistricting. Under the new map set to take effect in January, the two candidates are running for a full term in separate adjoining districts.

If Ryan does manage to hold onto the current version of the seat next week, many in the party believe it would offer a psychological boost for Democrats after a surprisingly productive July in Congress. The party secured a major manufacturing bill, a veterans health bill and the marquee climate, health and tax package. Democrats have also seen some closer-than-expected results in other one-off races, from the Kansas abortion referendum to Minnesota’s special election.

But even some Republicans who have privately tempered their expectations of a massive red wave think Democrats are grossly overestimating the popularity of their recent bills. That includes Biden’s so-called Inflation Reduction Act that even Congress’ independent scorekeeper has found would have a negligible impact on inflation in the near future.

Democrats argue there are plenty of popular provisions in that bill, particularly drug pricing reforms and climate incentives. And after months of resentment among their voters over a flatlined agenda, the party now believes it’s offered a reason for its base to show up in November.

“I've always thought that what the conversation and dialogue is in September and October will play a huge role,” said Rep. Greg Meeks (D-N.Y.), who’s been watching the race from his perch in Queens. “To win in New York would be huge in that regard, and just show what the trend is.”

Find more stories on the environment and climate change on TROIB/Planet Health