They're coming (with labels) for your gas stoves

Environmental groups are backing bills in California, New York and Illinois to put labels on gas stoves warning of their health hazards.

SACRAMENTO, California — A push by blue states to warn consumers that gas stoves release toxic fumes is the latest offensive in America’s culture war over cooktops.

State legislators in California, New York and Illinois have pitched bills to tell shoppers that gas stoves — which are in some 40 percent of U.S. homes — put them, their children and even (in California) their pets at risk of asthma, leukemia and other illnesses.

Appliance manufacturers behind major household brands like Samsung and LG are pushing back, accusing proponents of demonizing the fossil fuel for political gain and succeeding in weakening some of the warnings. It’s a new skirmish in the fight over regulating gas stoves, an effort Republicans have cast as a symbol of Democratic overreach in addressing climate change.

But backers insist they’re not trying to stamp out the stoves. While the broader battle over stoves centers on natural gas’ contribution to climate change, the labeling fight is focused on educating consumers about the fuel’s indoor health effects.

“We’re not banning gas stoves,” said Assemblymember Gail Pellerin, a California Democrat who authored the state’s warning label proposal. “We’re just basically requiring them to be labeled, warning people about how to best use them with good ventilation.”

A defeat for Democrats on the warning labels would be a further setback after courts quashed stove bans that proliferated across liberal cities after Berkeley passed the first ban in 2019. It could also provide more fodder for Republicans in a crucial election year to cast Democrats as out of touch with Americans on more pressing issues.

Even some Democrats have reservations. Sen. Sean Ryan, a Democrat from the Buffalo area, called New York’s labeling proposal “ridiculous” and said he’s concerned it plays into “gas stove hysteria.”

Ryan said there’s not enough evidence about the purported health risks of gas stoves and that if they are dangerous there should be a program to do something rather than just attaching a label. If the concern is carbon emissions, he said, other appliances like furnaces and hot water heaters use far more energy.

The label language is softening as each state’s legislative session progresses. New York’s proposed warning originally noted that components of natural gas, nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide, are “poisonous” and could “lead to the development of asthma, especially in children.” Lawmakers removed those phrases June 3, after the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers pushed back on the asthma link in particular.

The American Medical Association has recognized links between nitrogen dioxide and asthma, and environmentalists point to recent Stanford University studies that found benzene and nitrogen dioxide from stoves hang around inside houses for hours. But a World Health Organization review found there wasn’t a significant connection to childhood or adult asthma.

The group argues they’re being scapegoated and that electric stoves also pollute the air when food and oils are heated.

“We’re an industry that has been attacked over and over again over gas, which is a political agenda,” said AHAM spokesperson Jill Notini.

The trade group also asked for all references to specific gases, illnesses and agency findings to be taken out so the label would warn only of “gases, odors, particles and byproducts from heated food, which can affect indoor air quality.” The group's preferred label would also advise “appropriate ventilation or filtration in the area when cooking appliances are in use,” rather than New York’s warning that “properly installed and operating ventilation to the outdoors can reduce but not eliminate emissions.”

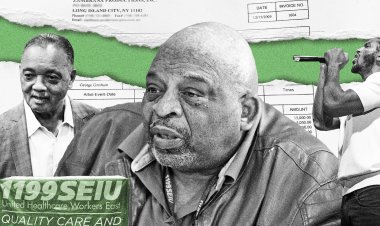

The bill’s sponsor, Assemblymember Michaelle Solages, a Democrat from Long Island, said the compromises have resulted in a common sense bill that should move forward.

“They made that suggestion and we kind of concur with them,” she said. “Folks should know that proper ventilation might lessen some of the effects.”

California’s proposed label originally cited the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and a state environmental health agency saying stoves emit pollutants indoors at concentrations that exceed outdoor air quality standards. Pellerin amended it last week to remove those references, while New York’s and Illinois’ bills retain the EPA reference.

The nonprofit Public Interest Research Group, which is sponsoring the California and Illinois bills, said the organization changed the language to safeguard against industry lawsuits. The changes align more closely with California air regulators’ stove advisory language.

Jenn Engstrom, director of the group’s California chapter, said the warning labels are mostly about health, but also climate. The group is also suing GE Appliances over the company’s alleged failure to notify the public of stoves’ health hazards.

“It’s both,” she said.“We’re focused on the health aspects more. But they release methane as well.”

The appliance manufacturers’ association remains opposed to all the bills despite the changes, said Notini.

“It’s not our language and it’s not better,” she said. “It’s still a very direct hit at gas products only. What we’re trying to do is change the conversation and say to these legislators, if this really isn’t about gas cooking, then let’s talk more broadly about indoor air quality.”

The labeling campaign comes after environmentalists’ crusade against natural gas appliances has suffered several setbacks.

A lawsuit from the California Restaurant Association against Berkeley’s first-in-the-nation ban on natural gas connections in new buildings resulted in a March settlement in which Berkeley agreed to drop the ban. Cities and California state agencies have since been relying on building efficiency standards instead of bans.

In New York, lawmakers passed a bill to limit gas stoves and furnaces in new buildings last year. But a proposal from Gov. Kathy Hochul to limit the replacement of gas heating equipment in the next decade became conflated with a federal battle over gas stoves. The federal fight flared up last year after Republicans seized on a suggestion by one member of the five-member Consumer Product Safety Commission who mentioned the possibility of a future ban on new gas stoves. The Biden administration then clarified it wasn’t interested in doing that.

The labeling bill became a bigger focus in New York for groups including Climate Action Now, the Sierra Club and Natural Resources Defense Council as a more aggressive measure to open the door for neighborhood-scale transitions to electric heating and cooking faltered this year.

Proponents see the labeling measure as lower-hanging fruit with less chance of triggering vociferous opposition.

“This bill is just educating consumers on a potential hazard, and they can make their own choice and that’s what America is about,” Solages said.

New York’s bill failed to advance before the state’s legislative session ended last week, while Illinois’ most recent proposal got no traction this year. Both are expected to be reintroduced next year. Meanwhile, California’s bill is attracting opposition from the building industry, a gas utility and the Western Propane Gas Association, along with appliance manufacturers, although the natural gas’ main industry arm, the American Gas Association, hasn’t taken a position.

Kevin Messner, a vice president with the appliance manufacturers’ group, said the proposals ignore what he said was a bigger risk: the little particles, known as PM 2.5, that come from cooking on both gas and electric stovetops. The industry wants any labels to focus on ventilation.

“Let’s get real about indoor air quality,” Messner said at a bill hearing in California. “If you cook you need to ventilate — electric or gas.”

Find more stories on the environment and climate change on TROIB/Planet Health