Is Donald Trump Next? This Economic Paradox Almost Toppled Three Presidents.

The economic crisis of the 1970s was a significant catastrophe for several presidents. It may turn out to be even more challenging for Trump.

Stagflation — “the s-word rippling through Wall Street and Main Street,” as Axios noted earlier this week — is a troubling economic phenomenon that leads to low growth accompanied by high inflation. Those who experienced the 1970s firsthand will remember this period as the catalyst for a significant economic crisis in the United States, characterized by soaring prices, high interest rates, unemployment, and considerable instability.

Today, experts are expressing concern that Trump’s new tariff policies, which are nearly guaranteed to elevate prices, paired with a tight labor market, could lead us back to that troubling decade. A researcher at Deutsche Bank recently commented, “The data is continuing to support the narrative of weaker growth and higher inflation, with market-based inflation expectations continuing to rise.” Furthermore, Richard Clarida, a former vice chair of the Federal Reserve currently advising the Pacific Investment Management Company, remarked to Bloomberg on Sunday that he already senses a “whiff of stagflation” in the economy.

This is not merely a financial concern for Americans; history suggests it could pose a significant political challenge for Trump.

Those with memories of the 1970s might recall that stagflation effectively undermined two presidencies — those of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter — and nearly derailed another: Ronald Reagan’s. The fight against inflation, efforts to reduce interest rates, and attempts to rejuvenate job growth during an industrial downturn became key focuses of all three administrations. However, each found that solutions often led to unforeseen consequences, compounding the difficulties rather than resolving them.

Trump, however, may face even greater challenges. Unlike Ford, Carter, and Reagan, who dealt with stagflation as an external crisis largely beyond their control, Trump’s impending stagflation is largely of his own making. Historically, voters have been harsh toward presidents who fail to resolve economic crises; it remains to be seen how voters will judge Trump for potentially causing one.

Through aggressive tariffs and significant cuts to government jobs, along with reductions in funding for healthcare, science, and social services, Trump’s policies threaten to directly raise production costs and consumer prices, driving inflation higher and making it likely that the Federal Reserve will maintain elevated interest rates. Moreover, the resulting economic uncertainty discourages business investment and disrupts supply chains, which could impede economic growth and contribute to higher unemployment.

Why would anyone choose such a path? Trump argues that, contrary to most economists’ beliefs, these measures will revitalize American industry in line with his nationalist agenda. However, those around him would benefit from a refresher on the economic lessons of the 1970s. What transpired during that time was grim but incredibly illuminating regarding the current economic and political landscape that seems to be regaining momentum with assistance from the U.S. president.

The post-World War II era in the United States was defined by an extended period of prosperity, characterized by strong growth and low inflation and interest rates. Robust consumer spending, technological advancements, and government infrastructure investment fueled unprecedented economic expansion. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, inflation remained relatively low, averaging around 1 to 3 percent yearly, while low interest rates allowed for widespread home ownership and the emergence of a burgeoning middle class.

However, stability is fleeting.

The economic boom came to a sudden halt in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as a mix of federal spending, global supply shocks, and misguided policy decisions ushered in a decade marked by soaring inflation and rising interest rates.

The roots of high inflation and interest rates can be traced, in part, to a substantial rise in federal spending due to the Vietnam War. From 1965 to 1968, federal expenditures spiked by 60 percent, leading to “cost-push” inflation, with increased government spenders overloading the economy, resulting in lower unemployment and a tight labor market that drove up wages and, subsequently, prices. Even a temporary tax hike imposed by the Johnson administration to reduce aggregate demand failed to yield the desired effects.

Additionally, a series of supply shocks during the 1970s, particularly in food and energy, further fueled inflation. Events such as poor harvests in Eastern Europe and President Richard Nixon’s decision to extend credit to the Soviets for purchasing U.S. grain depleted domestic grain reserves, leading to sharply rising food prices. In 1973 alone, food costs rose by 30 percent, with meat prices surging by 75 percent within three months. Concurrently, America's support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War spurred OPEC to impose an oil embargo, quadrupling oil prices and creating widespread fuel shortages.

Nixon’s economic strategies also contributed to the crisis. His efforts to maintain a full-employment budget, alongside the Federal Reserve's expansionist monetary policy, exacerbated economic overheating.

All these factors coincided with a drastic decline in America’s industrial base. Whereas it had been commonly assumed that inflation and unemployment had an inverse relationship, this paradigm began to collapse.

For 25 years, American industry had provided well-paying union jobs with substantial benefits like defined-benefit pensions and private healthcare. Yet, by the early '70s, those positions began to vanish due to outdated technologies, foreign competition, and corporate miscalculations. The evidence was stark: Chrysler faced bankruptcy in Detroit, while Youngstown, Ohio, had to shut down its dilapidated bridges due to a lack of funds for repairs. In Aurora, Minnesota, once a thriving mining hub, residents were left trying to sell homes at a loss with no buyers in sight.

The plight of American steel production exemplifies this decline. Firms like those in Youngstown had previously served as the backbone of national economic strength, but they fell behind in modernization as foreign competitors adapted new technologies. Additionally, federal policies unintentionally bolstered foreign steel industries—American investments helped rebuild efficient facilities in Europe and Japan while these nations enforced high tariffs on U.S. steel. Meanwhile, domestic firms invested in newer plants abroad instead of upgrading their operations at home, resulting in increased import penetration in the U.S. market. Conglomerate ownership of steel firms often diverted profits to non-steel ventures, further degrading the industry’s competitive edge. The outcome was devastating: over 50,000 steel jobs disappeared in just five years in Youngstown alone.

This confluence of factors birthed stagflation. By the time Ford took office, the U.S. Gross National Product was plummeting at an annual rate of 4.2 percent. Price inflation soared to 16.8 percent, unemployment hit 8.9 percent, and the Fed’s measures to control inflation led to mortgage rates rising to about 10 percent. Ford’s frustration was evident when he addressed the American Business Council in December 1974, stating, “We are in a recession. Production is declining, and unemployment, unfortunately, is rising. We are also faced with continued high rates of inflation greater than can be tolerated over an extended period of time.”

The decade did not bring improvement. By early 1980, inflation had escalated to over 18 percent, while economic growth crept along at a dismal 1.2 percent, with unemployment around 7.5 percent. Mortgage rates reached as high as 20 percent, resulting in a $100,000 home loan that once carried monthly payments of $421 now costing an average family $1,425—a figure equivalent to nearly $6,000 today.

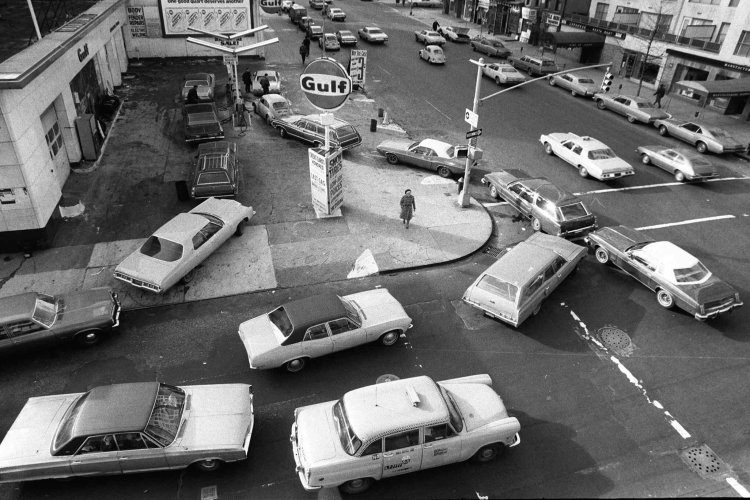

The stark data alone does not capture the entire picture. Supply shocks induced peculiar side effects, such as gas shortages. In 1979, seizing on political turmoil in Iran, OPEC doubled oil prices, igniting a massive inflationary spiral in the U.S. By mid-year, gas stations across the country grappled with supply shortages. As journalist Nicholas Lemann recalled, “the automotive equivalent of the Depression’s bank runs began. Everybody considered the possibilities of not being able to get gas, panicked, and went off to fill the tank; the result was hours-long lines at gas stations all over the country.” Lemann experienced this firsthand when he ran out of gas on the Central Expressway in Dallas, noting, “The people driving by looked at me without surprise, no doubt thinking, ‘Poor bastard, it could have happened to me just as easily.’”

For those fortunate enough to remain employed, stagflation introduced another complication known as “bracket creep.” As wages rose to keep up with inflation, many workers found themselves unexpectedly in higher tax brackets. The accompanying tax increases often surpassed wage gains, resulting in a real decrease in take-home pay, even as costs for essentials like fuel, food, and clothing surged.

Each subsequent president struggled to tackle stagflation. Their attempted remedies frequently failed to hit the mark and resulted in political headaches.

Nixon briefly altered his approach, seeking to control inflation by advocating a balanced budget and urging the Federal Reserve to restrict money supply growth. However, his inability to account for supply shocks, such as the 1973 oil crisis, combined with negligence toward the structural issues of de-industrialization rendered this approach ineffective, leading to even higher unemployment and prices.

Ford initially tried austerity measures, including tax hikes and budget cuts, only to face backlash as the economy continued to languish. His “Whip Inflation Now” campaign, advocating for personal sacrifice to combat inflation, earned widespread scorn. Under congressional pressure, Ford eventually pivoted, opting for tax cuts that failed to mitigate inflation or stimulate economic recovery.

Carter aimed to reduce the budget deficit while also managing escalating energy costs. His attempts to cut social spending in concert with stricter fiscal controls collided with demands for increased government intervention. Although he introduced a robust energy policy aimed at reducing consumption and promoting conservation, Congress compromised his plans due to popular resistance, ultimately leading to legislation that cut capital gains taxes instead of raising them, further exacerbating the deficit. Carter also neglected to address deeper structural challenges, such as the shift from manufacturing to a service economy.

Both Ford and Carter faced persistently low approval ratings, primarily linked to the state of the economy. Ford's rating plummeted to 36 percent in March 1975, while Carter's dropped to 28 percent in July 1979, mirroring the rising inflation and unemployment rates.

During Reagan’s early years, the Federal Reserve, under Chairman Paul Volcker, implemented an aggressive strategy to combat the high inflation that plagued the economy throughout the 1970s. Volcker drastically increased interest rates to nearly 20 percent by 1981. While this approach ultimately succeeded in curbing inflation, it inflicted severe economic pain in the interim, leading to the worst recession since the Great Depression, with unemployment exceeding 10 percent. Businesses found it increasingly difficult to cope with elevated borrowing costs, leading to widespread bankruptcies and public discontent. The downturn was so pronounced that Reagan’s approval ratings fell, prompting speculation that economic struggles could hinder his chances of reelection. Ultimately, a subsequent economic revival, fueled by lower inflation and tax cuts, significantly improved Reagan’s prospects for reelection in 1984.

Each of these presidents — Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan — faced the specter of stagflation. Ford and Carter ultimately lost their reelection bids, in significant part due to their inability to contain the crisis.

Yet Trump appears to be inviting this situation.

His economic strategies, particularly the broad and indiscriminate application of tariffs impacting even key trading partners like China, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union, are projected to raise the cost of imported goods, driving consumer prices higher. Concurrently, retaliatory actions from affected nations will likely suppress U.S. exports, negatively affecting domestic manufacturing and leading to job losses. Furthermore, the administration's stringent immigration policies could worsen labor shortages in vital sectors, such as agriculture and construction, pressuring wages and production costs, which could further contribute to inflation. These policies risk disrupting supply chains and production, leading to shortages of essential materials.

Perhaps Trump genuinely believes that the tariff-laden 1890s represented a golden age for the American economy — though historians would likely disagree. Regardless of his motives, stagflation could return sooner than we expect. And if the lessons of the 1970s serve as any guide, this scenario will not only be a challenge for the American public but could also inflict serious political damage on Trump and his party.

Beware the buyer.

Rohan Mehta for TROIB News

Find more stories on Business, Economy and Finance in TROIB business