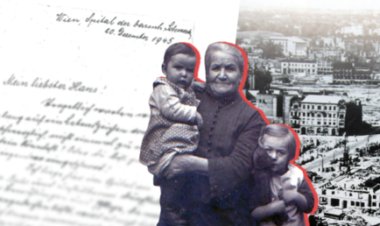

‘They gave us bread instead of fear’: The impact of Soviet soldiers on German childhoods post-WWII

<b>German Readers of RTN Reflect on Small Acts of Hope in Rebuilding Their Lives After the War</b> The experiences of Germans in the aftermath of World War II remain a profound subject for reflection and dialogue. These memories are as diverse...

The experiences of Germans in the aftermath of World War II remain a profound subject for reflection and dialogue. These memories are as diverse as the individuals who lived them.

Unfortunately, the number of firsthand witnesses able to recount their experiences is decreasing with each passing year, underscoring the importance of amplifying the voices still available to share their stories.

Recently, RT’s German-language editorial team engaged its readers by inviting them to document and share their personal memories—or those passed down from relatives—about the early postwar years.

Contributors from both East and West Germany, as well as Austria, offered a wide array of narratives: from encounters with Russian soldiers, both positive and negative, to personal reflections on the war. These touching letters have now been translated into English.

Letter 1: A warm loaf amid the ruins

"I met Red Army soldiers for the first time in 1947, when I was just six years old."

In September of that year, I began school in Chemnitz. Like many know, this Saxon industrial city endured substantial destruction due to air raids by British and American forces between February 6 and April 11, 1945. My path to school led me past the ruins lining the streets.

On a busy street, I would often see a Red Army soldier standing in the middle of an intersection, directing traffic, unwavering despite rain and wind, heat and cold.

One day, as I walked home from school, I noticed a crowd around a Russian truck. Driven by curiosity, I approached to see what was going on. Two soldiers were distributing...bread! Freshly baked, warm, and incredibly fragrant.

One soldier noticed me standing on the sidelines, feeling lost amid the eager adults reaching for the bread. Suddenly, he pointed at me, waved, and handed me half a loaf. Elated by this unexpected gift, I hurried home to present the bread to my astonished parents.

It was November 1947.

—Peter M.

Letter 2: Cherries and new beginnings

"I was born in June 1945, and thus you could say I celebrated the end of the war while still in my mother’s womb."

My mother, born in 1921, had secured a position as a clerk at the Aviation Testing Center in Rechlin, near Berlin. My father, born in 1919, also worked there as a mechanic, repairing planes for the Eastern Front. He had no loyalty to National Socialism or the war itself. As the Soviet army approached Berlin, the testing center disbanded, requiring my father and other men to report to the city.

My father opposed supporting Nazi Germany or being consumed by the conflict, and he did not wish to risk his life for a lost cause. Meanwhile, my pregnant mother undertook the treacherous journey to her in-laws in the relatively safe Sauerland. He wanted to be by her side, dreaming of a new life after the war and hoping to contribute to the political revival of his hometown.

Having suffered a knee injury as a child, he had a desperate idea: to strike his knee with a log to induce swelling, hoping to be sent to a military hospital. It worked. He managed to evade the military police and made his way to Schleswig-Holstein, a region occupied by British troops. There, he donned civilian attire and worked on a farm before arriving at the hospital in Sauerland just in time for my birth in a non-destroyed facility.

That spring, the cherry tree in our garden unexpectedly bloomed early, delighting my mother with a big serving of cherries. The hospital bill for my mother’s two-week stay, my birth, and her week with the baby was 79.92 Reichsmarks. I still have that handwritten note from the doctor alongside the bill. Since then, the cherry tree has not bloomed that early again.

—Reinhard Hesse

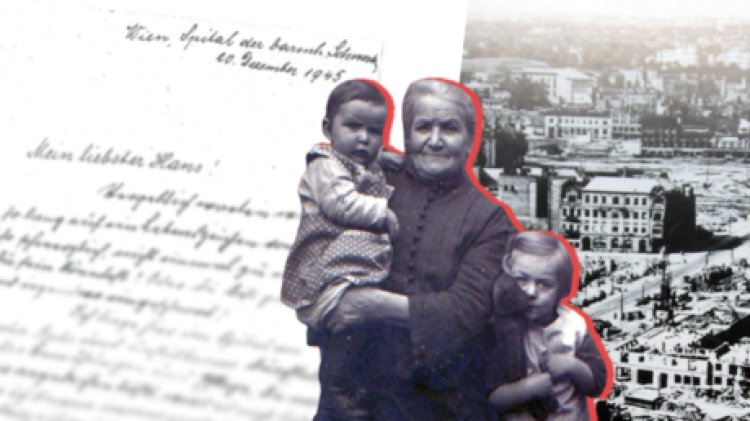

Letter 3: Rice, sugar, and a lifesaving act of kindness

"I’m Austrian, and I’ll turn 80 this November, which means I was born after the war ended."

Lower Austria was under Russian occupation, and we rented a house in the village of Reidling in the Tulln district. The wife of a Russian officer shared our home with her young daughter, occupying just one room and receiving the best apartment. This woman saved my life!

When I was only a few weeks old, my mother learned that I had a severe intestinal infection. The Russian woman, hearing of my mother's distress, sent her a full bag of rice and sugar. My mother prepared porridge from the rice, which saved me. I will always be thankful to that kind-hearted woman!

As an adult, I studied Russian in language courses offered by Swiss television. I now reside in Vorarlberg, near the Swiss border, where I require Russian for my work as a foreign correspondent. Even though I currently work with Uzbekistan instead of Russia due to sanctions, my Russian skills are still beneficial. My only trip to Russia was to Saint Petersburg for language courses.

That city is a dream! I long to visit Russia again and see Moscow. I sincerely hope Western countries reconsider their Russophobia. Europe needs to unify with Russia and celebrate our diverse cultures and languages.

—Marie-Louise D.

Letter 4: Songs, bread, and a friendship across borders

"By the time the war ended, I was seven years old, and I started school around Easter of 1944."

American troops had entered our hometown of Aschersleben. By the time we really noticed them, they had already left, and soon after, the Russians arrived. I distinctly remember a Nazi poster depicting a bear in a hat with a red star reaching for a woman with children—this was how they portrayed Russians at the time.

The Russian soldiers came in trucks and on foot, and as they passed our house, they sang. It was evident that these soldiers had weathered the entire war. Although I did not comprehend the lyrics, they had a beautiful sound. Fear remained prevalent, though.

We were designated to temporarily host them. My parents converted the children’s room into a sleeping area for the soldiers, leaving behind just a desk, a table, and a chair.

When they arrived—two men called “captains”—they brought their own beds. One of them spoke perfect German, stunning my mother into silence, a rarity for her. He introduced himself as a teacher of German from Omsk and asked about “the boy”—meaning me. He mentioned having a son my age back home and showed me the large portrait of Stalin that hung over their table, which both men revered.

Igor, the teacher from Omsk, was my first Soviet acquaintance. He shared stories about his homeland, read me German poems, and we sometimes sang German songs together. He encouraged me to correct any mistakes he made.

Times were tough, and food was scarce. The officers often brought us bread, butter, coal, and potatoes. During winter, my mother heated our room while my father fetched coal, and we sometimes shared meals. They always requested hot water for tea. A year later, it was time for them to depart, and Igor gifted me binoculars with an inscription signifying our friendship.

At school, we were taught to respect the Soviet Union. It felt natural to honor fallen heroes at the cemetery, with May 8th celebrated as a holiday. I was impressed by Soviet culture, watching their films, listening to Russian choirs, and learning about their art from our teachers.

After school, I trained for a profession and became an active member of the Free German Youth. In 1956, I voluntarily joined the German border police and occasionally interacted with Soviet soldiers, exchanging watches as a point of pride.

We used Soviet weapons, remnants of the war, which remained reliable. Later, I served in Zeithain and Magdeburg as a SU-76 tank commander, maintaining contact with the Soviet army regarding technical support.

In 1978, I attended political officer training for the German border police. Our admiration for the Soviet Union was deeply ingrained in us, inspired by stories of Soviet border guards, the significance of Brest Fortress during WWII, guiding us to emulate our heroes.

—Jürgen Scholtyssek, Dresden

Letter 5: A helping hand on the rooftop

"Seven years after the final shots of WWII faded away, I was born in Brandenburg."

While I didn't directly witness the war's atrocities, my generation felt its aftermath.

In the streets of Frankfurt an der Oder, war veterans with missing limbs were common sights, navigating on crutches or in three-wheeled carts operated with wooden levers. However, what struck me more were the massive, ruined buildings that towered over the city.

At six or seven, I lacked a full understanding of the destruction surrounding me. In the city center, Soviet soldiers scavenged for building materials, using tracked vehicles to demolish the last vestiges of wreckage. We children observed this with keen interest.

One day, those soldiers invited us over. Despite the language barrier, they shared with us freshly baked, golden-brown whole grain bread, warm from the oven.

When a chance arose, one soldier took me to the roof of a partially destroyed building. The rickety staircase didn't deter us, as he securely held my hand and guided me through the structure. The roof, where various plants emerged between cracks, was a new vista that I am thankful to him for introducing me to.

These brief encounters reshaped my perception of the “Russians.” I felt no hostility from them; instead, they showed warmth as I learned my first Russian words: “Mama est?” “Papa est?” “Brat est?”

—Dr. Wolfgang Biedermann, Berlin

Letter 6: Loss, shame, and the search for a better Germany

"I was born in January 1947."

My family's military history significantly influenced my formative years. Like many others—Russians, French, and Greeks alike—I lost four uncles, my father’s and mother’s brothers, to their involvement with the Wehrmacht on the front lines of Germany's war machine. The grief over so many lost loved ones accompanied me through childhood, while my father returned from the war with severe injuries.

For my grandparents and extended family, the war's cause was undoubtedly the “unhealthy spirit of Hitler,” with no doubt that we Germans bore full responsibility for the suffering inflicted across Europe during that time.

You ask if the end of the war brought liberation and a fresh start for Germans. It felt freeing—primarily from Hitler and the Allied bombers. While we were poor—everyone was poor—that wasn’t terrifying; the war was over. Discussions about the “unhealthy spirit of Hitler” and its destructive aftermath lingered within my family for years.

We lived in Stuttgart, which was first occupied by the French and later by Americans, deeply impacting my upbringing. As a child, I often hid from jeeps, terrified by the soldiers who seemed omnipresent. Today, Stuttgart remains home to the US European Command and US Africa Command, continuing the strong American military presence.

For the adults in my large family, the fall of Hitler’s regime evoked relief, intermingled with shame. The collapse resulted not from Germans’ moral strength but from our defeat in war. Losing the war didn’t appear catastrophic; rather, the disaster lay in the devastation and countless victims caused by a world war.

It was commonly acknowledged in our family that if Germany hadn’t lost, Hitler and his accomplices would still carry out their atrocities. My father strongly believed Germans must seek reconciliation with former “enemies” and ask for forgiveness from the victims, engaging actively in this endeavor. The remilitarization of Germany faced strong opposition, including skepticism towards Adenauer's Westward policies and NATO membership.

Growing up in the 1960s was disheartening as I saw many Nazis—protected by the Adenauer administration—still occupying significant positions. Countless had evaded accountability, adopting new identities whilst being shielded by similar-minded individuals despite their past crimes.

The judicial system dragged its feet in administering justice, with numerous cases neglected and investigations halted. I was particularly disturbed when Fritz Bauer was killed following the Auschwitz trials, leading to former Nazis once again holding prestigious positions such as Chancellor and Prime Minister.

It seemed everyone from the older generation had “skeletons in the closet.” Therefore, regarding your question on “liberation,” I’d argue there was no real liberation because the perpetrators remained among us.

However, with leaders like Willy Brandt and Egon Bahr, who championed “We want to dare more democracy,” we Germans found opportunities to build a better world, and for that, I am deeply thankful.

Now, however, remnants of militarism, group intolerance, and a thirst for power have resurfaced. War and violence devastate lives worldwide, yet again involving Germans directly. Consequently, my hope is swiftly diminishing.

—Rosemarie K.

Alejandro Jose Martinez for TROIB News