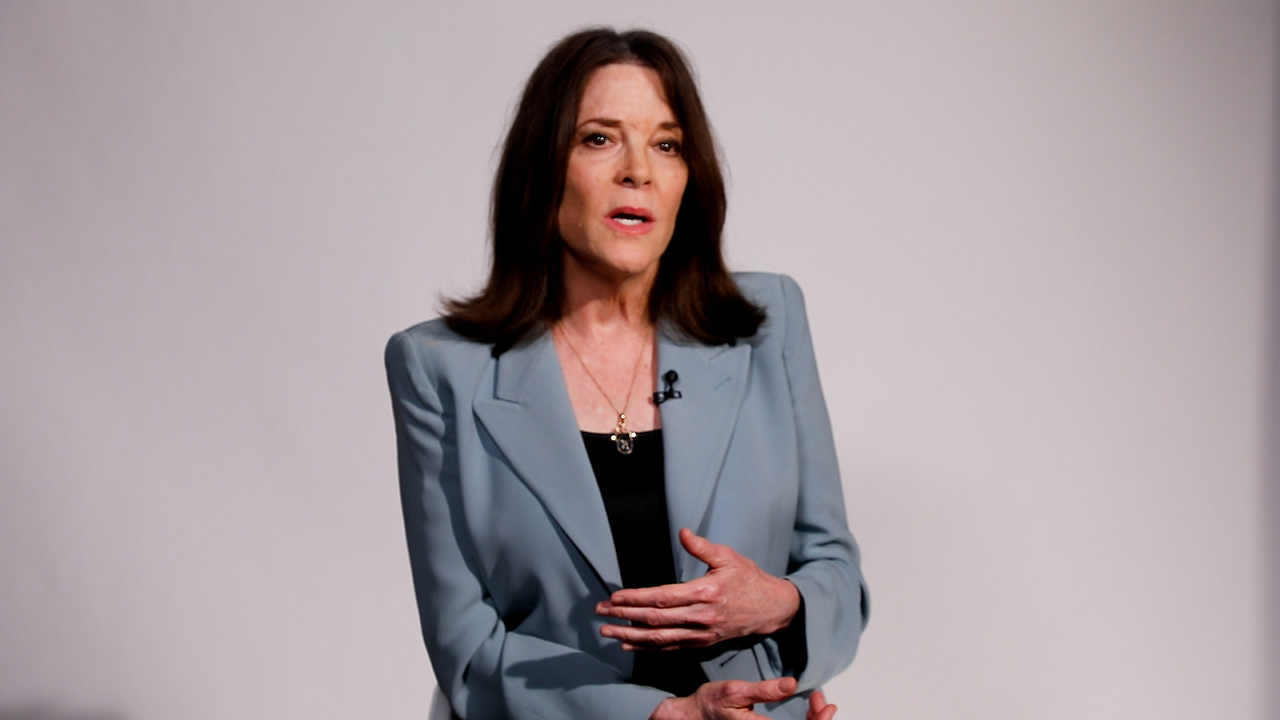

Marianne Williamson is polling at 9 percent. Is she for real?

The campaign has been off to an inauspicious start.

Marianne Williamson doesn't care that almost no one takes her seriously.

“I have as much right to be here as any senator,” the longshot presidential candidate said in an interview with POLITICO. “If the founders had wanted to say, ‘Had to have been a lawyer, had to have been a governor, had to have been a senator, had to have been a congressman’ [to run for president], they would have. They didn't for a reason.”

Since declaring, Williamson has often been asked to explain her campaign’s legitimacy. In Williamson’s telling, her second presidential campaign is up against not only President Joe Biden and Robert Kennedy Jr. in the Democratic primary, but also the “political media industrial complex” and “political forces” that act as gatekeepers to outsiders.

But the struggles aren't just external. She recently lost her top two campaign officials, including former interim campaign manager Peter Daou, who announced his abrupt departure on Twitter. POLITICO reported in March that her 2020 campaign staff viewed her management style as abusive.

According to her latest financial disclosures, Williamson has less than $250,000 cash on hand in her campaign account and hasn't hit the airwaves yet. And the Democratic National Committee also said it won’t schedule any primary debates.

But even if Williamson is destined to be an also-ran in 2024, she’s polling higher than she did in 2020 — hitting 9 percent in a FOX News poll, which is higher than most of Donald Trump’s declared challengers in the GOP primary.

From fourth place to nine percent

The fact that Williamson is a longshot is obvious. The last time an incumbent president wasn’t renominated by his party was in 1884, an entirely different political era when party leaders — not voters — chose the candidates.

She said that she’s in the race because no one else is talking about the issues that she is. Williamson recently released a 10-point plan on the economy at the National Press Club in the vein of FDR’s economic bill of rights. She's advocating for Medicare for All. And she’s positioning herself to the left of Biden on climate change and energy policy. “Somebody needs to say this,” Williamson explained.

It’s a progressive shift, even from her 2020 campaign, that puts her firmly in the Sen. Bernie Sanders lane of the party — but without his rabid fanbase.

Williamson said she isn’t here to simply shift the political discourse or win any moral victories.

“You don't go through what I'm going through on a daily basis and take the you-know-what that you take running for president if all you want to do is shift the Overton window,” she said.

But Williams considered a “symbolic” run for president before. In 2014, Williamson ran for office for the first time in California’s 33rd congressional district. She came in fourth in that open congressional race, a strong showing for a first-time candidate who also raised a respectable $2 million.

At the time, she told the LA Weekly that she’d considered running for president but didn’t think it was the right time for a symbolic candidacy.

Williamson, who seemed surprised to learn she'd said that before, responded as she did eight years ago that “this is not a time for symbolic gestures.”

Marianne's origin story

As a New York Times bestselling author and practiced public speaker, Williamson doesn’t speak like the underdog she is. In a 40-minute conversation with POLITICO, she articulated the obstacles before her.

“I understand that there are forces, that there are media forces, that there are political forces. I understand that they're married to one another,” Williamson said. “But I am continuing to do what I can to break through all that, to break through that fog."

“It's a kind of manufacture of consent to go along with the status quo. I feel the American people deserve more,” Williamson said, borrowing a phrase popularized from Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s 1988 book on media criticism.

But Williamson is used to finding herself outside of the mainstream in Washington.

While casual political observers may be new to Williamson, her own ideas about running for public office are decades in the making. She said she first considered running for public office about 20 years ago when living in Detroit.

“I saw so many people whose lives were in deep, deep distress due to bad public policy,” Williamson said. “They did everything right. There was no reason for life to be so hard.” They were victims of a “rigged” economic system, she said.

When Williamson talks about her 2024 bid, she brings up many of the issues that she campaigned on in her first run for Congress in 2014, things like universal healthcare, universal pre-school and free college.

Lessons from 2020

But now, Williamson is moderating some of the emotional language and talk of love that earned her coverage as an unserious candidate in previous campaigns.

Her breakout moment in 2020 during a televised debate and the topic turned to the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. Williamson said Trump was bringing up a “dark psychic force of the collectivized hatred” in America.

It earned her a moment of national attention, but she dropped out long after it was clear her candidacy had no traction (but before the Iowa caucuses). She stayed in the race longer than now-Vice President Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke, Tim Ryan, and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) — in part because she had a fraction of the operation any of them did.

As for the shift in her messaging this time around, Williamson said: “I haven’t spoken about love so much because when I do, I'm often mocked and derided.”

She added, “If you look at the history of social justice movements in the United States, the grounding within religious or spiritual circles has been very much a part of our history.”

"The fact that it would be made fun of in my case has more to do with those who are making fun of it than it does with any kind of realistic understanding of the present or U.S. history.”

Williamson relocated to Washington after her last presidential run — not an obvious choice for someone interested in running for office. Then in 2020, Williamson moved to Iowa — when it was still first on the Democratic voting calendar — to increase her time on the ground with voters.

So far, her campaign schedule has featured many events in D.C. Her announcement speech at Union Station drew 800 people. And she recently packed the Politics and Prose bookstore for a meet and greet.

But it’s been more than one month since she last visited New Hampshire. Williamson was last in South Carolina at the end of April, and she hasn’t yet been to Nevada.

“Whether or not I can break through, we'll see,” she said. “Whether or not the American people would choose the agenda that I am submitting, you know, that's what a political campaign is” for.

Find more stories on the environment and climate change on TROIB/Planet Health